I Tuskegee Airmen - Myouth - Ricordi degli anni '70

Menu principale:

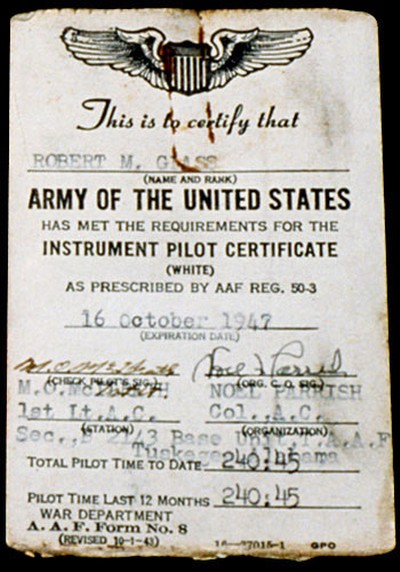

I Tuskegee Airmen

Modellismo > Aerei > North American P-51D "Mustang"

Tuskegee Airmen

The Stearman Kaydet training aircraft used by the Tuskegee Airmen, bearing the name Spirit of Tuskegee

Fonte: Wikipedia

Major James A. Ellison returns the salute of Mac Ross, as he reviews the first class of Tuskegee cadets; flight line at U.S. Army Air Corps basic and advanced flying school, with Vultee BT-13trainers in the background, Tuskegee, Alabama, 1941

Fonte: Wikipedia

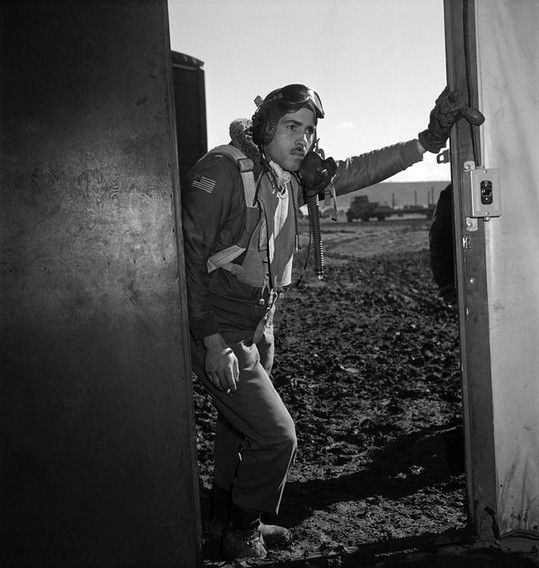

Portrait of Tuskegee airman Edward M. Thomas by photographer Toni Frissell, March 1945

Fonte: Wikipedia

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of primarily African-American military pilots (fighter and bomber) and airmen who fought in World War II. They formed the332nd Expeditionary Operations Group and the 477th Bombardment Group of the United States Army Air Forces. The name also applies to the navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, instructors, crew chiefs, nurses, cooks and other support personnel.

All black military pilots who trained in the United States trained at Griel Field, Kennedy Field, Moton Field, Shorter Field and the Tuskegee Army Air Fields. They were educated at Tuskegee University (formerly Tuskegee Institute), located near Tuskegee, Alabama. Of the 922 pilots, five were Haitians from the Haitian Air Force and one pilot was from Trinidad. It also included a Hispanic or Latino airman born in the Dominican Republic.

The 99th Pursuit Squadron (later the 99th Fighter Squadron) was the first black flying squadron, and the first to deploy overseas (to North Africa in April 1943, and later to Sicily and Italy). The 332nd Fighter Group, which originally included the 100th, 301st and 302nd Fighter Squadrons, was the first black flying group. It deployed to Italy in early 1944. Although the 477th Bombardment Group trained with North American B-25 Mitchell bombers, they never served in combat. In June 1944, the 332nd Fighter Group began flying heavy bomber escort missions and, in July 1944, with the addition of the 99th Fighter Squadron, it had four fighter squadrons.

The 99th Fighter Squadron was initially equipped with Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighter-bomber aircraft. The 332nd Fighter Group and its 100th, 301st and 302nd Fighter Squadrons were equipped for initial combat missions with Bell P-39 Airacobras (March 1944), later with Republic P-47 Thunderbolts (June–July 1944) and finally with the aircraft with which they became most commonly associated, the North American P-51 Mustang (July 1944). When the pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group painted the tails of their P-47s red, the nickname "Red Tails" was coined. The red markings that distinguished the Tuskegee Airmen included red bands on the noses of P-51s as well as a red rudder; the P-51B and D Mustangs flew with similar color schemes, with red propeller spinners, yellow wing bands and all-red tail surfaces.

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African-American military aviators in the United States Armed Forces. During World War II, black Americans in many U.S. states were still subject to the Jim Crow laws and the American military was racially segregated, as was much of the federal government. The Tuskegee Airmen were subjected to discrimination, both within and outside the army.

Origins

Background

Before the Tuskegee Airmen, no African-American had been a U.S. military pilot. In 1917, African-American men had tried to become aerial observers but were rejected. African-American Eugene Bullard served in the French air service during World War I because he was not allowed to serve in an American unit. Instead, Bullard returned to infantry duty with the French.

The racially motivated rejections of World War I African-American recruits sparked more than two decades of advocacy by African-Americans who wished to enlist and train as military aviators. The effort was led by such prominent civil rights leaders as Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, labor union leader A. Philip Randolph and Judge William H. Hastie. Finally, on 3 April 1939, Appropriations Bill Public Law 18 was passed by Congress containing an amendment by Senator Harry H. Schwartz designating funds for training African-American pilots. The War Department managed to put the money into funds of civilian flight schools willing to train black Americans.

War Department tradition and policy mandated the segregation of African-Americans into separate military units staffed by white officers, as had been done previously with the 9th Cavalry, 10th Cavalry, 24th Infantry Regiment and 25th Infantry Regiment. When the appropriation of funds for aviation training created opportunities for pilot cadets, their numbers diminished the rosters of these older units. In 1941, the War Department and the Army Air Corps, under pressure —three months before its transformation into the USAAF — constituted the first all-black flying unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

Because of the restrictive nature of selection policies, the situation did not seem promising for African-Americans, since in 1940 the U.S. Census Bureau reported there were only 124 African-American pilots in the nation. The exclusionary policies failed dramatically when the Air Corps received an abundance of applications from men who qualified, even under the restrictive requirements. Many of the applicants already had participated in the Civilian Pilot Training Program, unveiled in late December 1938 (CPTP). Tuskegee University had participated since 1939.

Testing

The U.S. Army Air Corps had established the Psychological Research Unit 1 at Maxwell Army Air Field, Montgomery, Alabama, and other units around the country for aviation cadet training, which included the identification, selection, education, and training of pilots, navigators and bombardiers. Psychologists employed in these research studies and training programs used some of the first standardized tests to quantify IQ, dexterity and leadership qualities to select and train the best-suited personnel for the roles of bombardier, navigator, and pilot. The Air Corps determined that the existing programs would be used for all units, including all-black units. At Tuskegee, this effort continued with the selection and training of the Tuskegee Airmen. The War Department set up a system to accept only those with a level of flight experience or higher education which ensured that only the most able and intelligent African-American applicants were able to join.

Airman Coleman Young, later the first African-American mayor of Detroit, told journalist Studs Terkel about the process:

They made the standards so high, we actually became an elite group. We were screened and super-screened. We were unquestionably the brightest and most physically fit young blacks in the country. We were super-better because of the irrational laws of Jim Crow. You can't bring that many intelligent young people together and train 'em as fighting men and expect them to supinely roll over when you try to fuck over 'em, right? (Laughs.)

First Lady's flight

The budding flight program at Tuskegee received a publicity boost when First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt inspected it on March 29, 1941, and flew with African-American chief civilian instructor C. Alfred "Chief" Anderson. Anderson, who had been flying since 1929 and was responsible for training thousands of rookie pilots, took his prestigious passenger on a half-hour flight in a Piper J-3 Cub. After landing, she cheerfully announced, "Well, you can fly all right."

The subsequent brouhaha over the First Lady's flight had such an impact it is often mistakenly cited as the start of the CPTP at Tuskegee, even though the program was already five months old. Eleanor Roosevelt used her position as a trustee of the Julius Rosenwald Fund to arrange a loan of $175,000 to help finance the building of Moton Field.

Formation

On 22 March 1941, the 99th Pursuit Squadron was activated without pilots at Chanute Field in Rantoul, Illinois.

A cadre of 14 black non-commissioned officers from the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments were sent to Chanute Field to help in the administration and supervision of the trainees. A white officer, Army Captain Harold R. Maddux, was assigned as the first commander of the 99th Fighter Squadron.

A cadre of 271 enlisted men begin training in aircraft ground support trades at Chanute Field in March 1941 until they were transferred to bases in Alabama in July 1941. The skills being taught were so technical that setting up segregated classes was deemed impossible. This small number of enlisted men became the core of other black squadrons forming at Tuskegee Fields in Alabama.

While the enlisted men were in training, five black youths were admitted to the Officers Training School (OTS) at Chanute Field as aviation cadets. Specifically, Elmer D. Jones, Dudley Stevenson and James Johnson of Washington, DC; Nelson Brooks of Illinois, and William R. Thompson of Pittsburgh, PA successfully completed OTS and were commissioned as the first Black Army Air Corps Officers.

In June 1941, the 99th Pursuit Squadron was transferred to Tuskegee, Alabama and remained the only Black flying unit in the country, but did not yet have pilots. The famous airmen were actually trained at five airfields surrounding Tuskegee University (formerly Tuskegee Institute)--Griel, Kennedy, Moton, Shorter and Tuskegee Army Air Fields. The flying unit consisted of 47 officers and 429 enlisted men and was backed by an entire service arm. On July 19, 1941, thirteen individuals made up the first class of aviation cadets (42-C) when they entered Preflight Training at Tuskegee Institute. After primary training at Moton Field, they were moved to the nearby Tuskegee Army Air Field, about 10 miles (16 km) to the west for conversion training onto operational types. Consequently, Tuskegee Army Air Field became the only Army installation performing three phases of pilot training (basic, advanced, and transition) at a single location. Initial planning called for 500 personnel in residence at a time.

By mid-1942, over six times that many were stationed at Tuskegee, even though only two squadrons were training there.

Tuskegee Army Airfield was similar to already-existing airfields reserved for training white pilots, such as Maxwell Field, only 40 miles (64 km) distant. African-American contractor McKissack and McKissack, Inc. was in charge of the contract. The company's 2,000 workmen, the Alabama Works Progress Administration, and the U.S. Army built the airfield in only six months. The construction was budgeted at $1,663,057. The airmen were placed under the command of Captain Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., one of only two black line officers then serving.

During training, Tuskegee Army Air Field was commanded first by Major James Ellison. Ellison made great progress in organizing the construction of the facilities needed for the military program at Tuskegee. However, he was transferred on 12 January 1942, reputedly because of his insistence that his African-American sentries and Military Police had police authority over local Caucasian civilians.

His successor, Colonel Frederick von Kimble, then oversaw operations at the Tuskegee airfield. Contrary to new Army regulations, Kimble maintained segregation on the field in deference to local customs in the state of Alabama, a policy that was resented by the airmen. Later that year, the Air Corps replaced Kimble. His replacement had been the director of training at Tuskegee Army Airfield, Major Noel F. Parrish. Counter to the prevalent racism of the day, Parrish was fair and open-minded and petitioned Washington to allow the Tuskegee Airmen to serve in combat.

The strict racial segregation the U.S. Army required gave way in the face of the requirements for complex training in technical vocations. Typical of the process was the development of separate African-American flight surgeons to support the operations and training of the Tuskegee Airmen. Before the development of this unit, no U.S. Army flight surgeons had been black.

Training of African-American men as aviation medical examiners was conducted through correspondence courses until 1943, when two black physicians were admitted to the U.S. Army School of Aviation Medicine at Randolph Field, Texas. This was one of the earliest racially integrated courses in the U.S. Army. Seventeen flight surgeons served with the Tuskegee Airmen from 1941-49. At that time, the typical tour of duty for a U.S. Army flight surgeon was four years. Six of these physicians lived under field conditions during operations in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. The chief flight surgeon to the Tuskegee Airmen was Vance H. Marchbanks, Jr., MD, a childhood friend of Benjamin Davis.

The accumulation of washed-out cadets at Tuskegee and the propensity of other commands to "dump" African-American personnel on the post exacerbated the difficulties of administering Tuskegee. A shortage of jobs for them made these enlisted men a drag on Tuskegee's housing and culinary departments.

Trained officers were also left idle, as the plan to shift African-American officers into command slots stalled, and white officers not only continued to hold command, but were joined by additional white officers assigned to the post. One rationale behind the non-assignment of trained African-American officers was stated by the commanding officer of the Army Air Forces, General Henry "Hap" Arnold: "Negro pilots cannot be used in our present Air Corps units since this would result in Negro officers serving over white enlisted men creating an impossible social situation."

Combat assignment

The 99th was finally considered ready for combat duty by April 1943. It shipped out of Tuskegee on 2 April, bound for North Africa, where it would join the 33rd Fighter Group and its commander, Colonel William W. Momyer. Given little guidance from battle-experienced pilots, the 99th's first combat mission was to attack the small strategic volcanic island of Pantelleria, code name Operation Corkscrew, in the Mediterranean Sea to clear the sea lanes for the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The air assault on the island began 30 May 1943. The 99th flew its first combat mission on 2 June. The surrender of the garrison of 11,121 Italians and 78 Germans due to air attack was the first of its kind.

The 99th then moved on to Sicily and received a Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC) for its performance in combat.

By the end of February 1944, the all-black 332nd Fighter Group had been sent overseas with three fighter squadrons: The 100th, 301st and 302nd.

Under the command of Colonel Davis, the squadrons were moved to mainland Italy, where the 99th Fighter Squadron, assigned to the group on 1 May 1944, joined them on 6 June at Ramitelli Airfield, nine kilometers south-southeast of the small city of Campomarino, on the Adriatic coast. From Ramitelli, the 332nd Fighter Group escorted Fifteenth Air Force heavy strategic bombing raids into Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Poland and Germany.

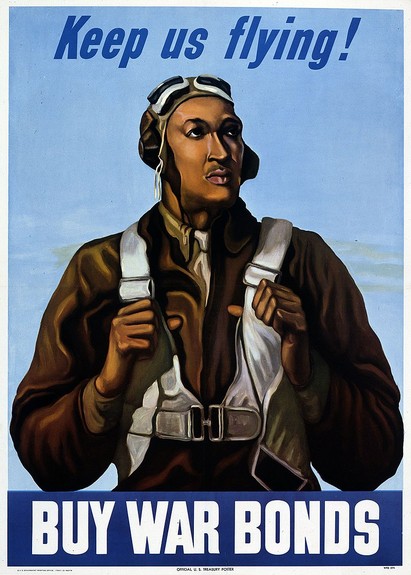

Flying escort for heavy bombers, the 332nd earned an impressive combat record. The Allies called these airmen "Red Tails" or "Red-Tail Angels", because of the distinctive crimson unit identification marking predominantly applied on the tail section of the unit's aircraft.

A B-25 bomb group, the 477th Bombardment Group, was forming in the U.S., but was not able to complete its training in time to see action. The 99th Fighter Squadron after its return to the United States became part of the 477th, redesignated the 477th Composite Group.

Active air units

The only black air units that saw combat during the war were the 99th Pursuit Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group. The dive-bombing and strafing missions under Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr. were considered to be highly successful.

In May 1942, the 99th Pursuit Squadron was renamed the 99th Fighter Squadron. It earned three Distinguished Unit Citations (DUC) during World War II. The DUCs were for operations over Sicily from 30 May–11 June 1943, Monastery Hill near Cassino from 12–14 May 1944, and for successfully fighting off German jet aircraft on 24 March 1945. The mission was the longest bomber escort mission of the Fifteenth Air Force throughout the war. The 332nd flew missions in Sicily, Anzio, Normandy, the Rhineland, the Po Valley and Rome-Arno and others. Pilots of the 99th once set a record for destroying five enemy aircraft in under four minutes.

The Tuskegee Airmen shot down three German jets in a single day. On 24 March 1945, 43 P-51 Mustangs led by Colonel Benjamin O. Davis escorted B-17 bombers over 1,600 miles (2,600 km) into Germany and back. The bombers' target, a massive Daimler-Benz tank factory in Berlin, was heavily defended by Luftwaffe aircraft, including propeller-driven Fw 190s, Me 163 "Komet" rocket-powered fighters, and 25 of the much more formidable Me 262s, history's first operational jet fighter. Pilots Charles Brantley, Earl Lane and Roscoe Brown all shot down German jets over Berlin that day. For the mission, the 332nd Fighter Group earned a Distinguished Unit Citation.

Pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group earned 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses. Their missions took them over Italy and enemy occupied parts of central and southern Europe. Their operational aircraft were, in succession: Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, Bell P-39 Airacobra, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and North American P-51 Mustang fighter aircraft.

Tuskegee Airmen bomber units

Formation

With African-American fighter pilots being trained successfully, the Army Air Force now came under political pressure from the NAACP and other civil rights organizations to organize a bomber unit. There could be no defensible argument that the quota of 100 African-American pilots in training at one time, or 200 per year out of a total of 60,000 American aviation cadets in annual training, represented the service potential of 13 million African-Americans.

On 13 May 1943, the 616th Bombardment Squadron was established as the initial subordinate squadron of the 477th Bombardment Group, an all-white group. The squadron was activated on 1 July 1943, only to be inactivated on 15 August 1943. By September 1943, the number of washed-out cadets on base had surged to 286, with few of them working. In January 1944, the 477th Bombardment Group was reactivated—an all-Black group. At the time, the usual training cycle for a bombardment group took three to four months.

The 477th would eventually contain four medium bomber squadrons. Slated to comprise 1,200 officers and enlisted men, the unit would operate 60 North American B-25 Mitchell bombers.The 477th would go on to encompass three more bomber squadrons–the 617th Bombardment Squadron, the 618th Bombardment Squadron, and the 619th Bombardment Squadron. The 477th was anticipated to be ready for action in November 1944.

The home field for the 477th was Selfridge Field, located outside Detroit, however, other bases would be used for various types of training courses. Twin-engine pilot training began at Tuskegee while transition to multi-engine pilot training was at Mather Field, California. Some ground crews trained at Mather before rotating to Inglewood. Gunners learned to shoot at Eglin Field, Florida. Bombers-navigators learned their trades at Hondo Army Air Field and Midland Air Field, Texas or at Roswell, New Mexico. Training of the new African-American crewmen also took place at Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Lincoln, Nebraska, and Scott Field, Belleville, Illinois. Once trained, the air and ground crews would be spliced into a working unit at Selfridge.

Command difficulties

The new group's first commanding officer was Colonel Robert Selway, who had also commanded the 332nd Fighter Group before it deployed for combat overseas. Like his ranking officer, Major General Frank O'Driscoll Hunter from Georgia, Selway was a racial segregationist. Hunter was blunt about it, saying such things as, "...racial friction will occur if colored and white pilots are trained together." He backed Selway's violations of Army Regulation 210-10, which forbade segregation of air base facilities. They segregated base facilities so thoroughly that they even drew a line in the base theater and ordered separate seating by races. When the audience sat in random patterns as part of "Operation Checkerboard," the movie was halted to make men return to segregated seating. African-American officers petitioned base Commanding Officer William Boyd for access to the only officer's club on base. Lieutenant Milton Henry entered the club and personally demanded his club rights; he was court-martialed for this.

Subsequently, Colonel Boyd denied club rights to African-Americans, although General Hunter stepped in and promised a separate but equal club would be built for black airmen. The 477th was transferred to Godman Field, Kentucky before the club was built. They had spent five months at Selfridge but found themselves on a base a fraction of Selfridge's size, with no air-to-ground gunnery range and deteriorating runways that were too short for B-25 landings. Colonel Selway took on the second role of commanding officer of Godman Field. In that capacity, he ceded Godman Field's officers club to African-American airmen. Caucasian officers used the whites-only clubs at nearby Fort Knox, much to the displeasure of African-American officers.

Another irritant was a professional one for African-American officers. They observed a steady flow of white officers through the command positions of the group and squadrons; these officers stayed just long enough to be "promotable" before transferring out at their new rank. This seemed to take about four months. In an extreme example, 22-year-old Robert Mattern was promoted to captain, transferred into squadron command in the 477th days later, and left a month later as amajor. He was replaced by another Caucasian officer. Meanwhile, no Tuskegee Airmen held command.

On 15 March 1945, the 477th was transferred to Freeman Field, near Seymour, Indiana. The white population of Freeman Field was 250 officers and 600 enlisted men. Superimposed on it were 400 African-American officers and 2,500 enlisted men of the 477th and its associated units. Freeman Field had a firing range, usable runways, and other amenities useful for training. African-American airmen would work in proximity with white ones; both would live in a public housing project adjacent to the base.

Colonel Selway turned the noncommissioned officers out of their club and turned it into a second officers club. He then classified all white personnel as cadre and all African-Americans as trainees. One officers club became the cadre's club. The old Non-Commissioned Officers Club, promptly sarcastically dubbed "Uncle Tom's Cabin", became the trainees' officers club. At least four of the trainees had flown combat in Europe as fighter pilots and had about four years in service. Four others had completed training as pilots, bombardiers and navigators and may have been the only triply qualified officers in the entire Air Corps. Several of the Tuskegee Airmen had logged over 900 flight hours by this time. Nevertheless, by Colonel Selway's fiat, they were trainees.

Off base was no better; many businesses in Seymour would not serve African-Americans. A local laundry would not wash their clothes and yet willingly laundered those of captured German soldiers.

In early April 1945, the 118th Base Unit transferred in from Godman Field; its African-American personnel held orders that specified they were base cadre, not trainees. On 5 April, officers of the 477th peaceably tried to enter the whites-only officer's club. Selway had been tipped off by a phone call and had the assistant provost marshal and base billeting manager stationed at the door to refuse the 477th officers entry. The latter, a major, ordered them to leave and took their names as a means of arresting them when they refused. It was the beginning of the Freeman Field Mutiny.

In the wake of the Freeman Field Mutiny, the 616th and 619th were disbanded and the returned 99th Fighter Squadron assigned to the 477th on 22 June 1945; it was redesignated the 477th Composite Group as a result. On 1 July 1945, Colonel Robert Selway was relieved of the Group's command; he was replaced by Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. A complete sweep of Selway's white staff followed, with all vacated jobs filled by African-American officers. The war ended before the 477th Composite Group could get into action. The 618th Bombardment Squadron was disbanded on 8 October 1945. On 13 March 1946, the two-squadron group, supported by the 602nd Engineer Squadron (later renamed 602nd Air Engineer Squadron), the 118th Base Unit, and a band, moved to its final station, Lockbourne Field. The 617th Bombardment Squadron and the 99th Fighter Squadron disbanded on 1 July 1947, ending the 477th Composite Group. It would be reorganized as the 332nd Fighter Wing.

War accomplishments

In all, 992 pilots were trained in Tuskegee from 1941–1946. 355 were deployed overseas, and 84 lost their lives. The toll included 68 pilots killed in action or accidents, 12 killed in training and non-combat missions and 32 captured as prisoners of war.

The Tuskegee Airmen were credited by higher commands with the following accomplishments:

- 1578 combat missions, 1267 for the Twelfth Air Force; 311 for the Fifteenth Air Force;

- 179 bomber escort missions, with a good record of protection, losing bombers on only seven missions and a total of only 27, compared to an average of 46 among other 15th Air Force P-51 groups

- 112 enemy aircraft destroyed in the air, another 150 on the ground and 148 damaged. This included three Me-262 jet fighters shot down;

- 950 rail cars, trucks and other motor vehicles destroyed (over 600 rail cars)

- One torpedo boat put out of action. The ship concerned was a World War I-vintage destroyer (Giuseppe Missori) of the Italian Navy, that had been seized by the Germans and reclassified as a torpedo boat, TA22. It was attacked on 25 June 1944 and damaged so severely she was never repaired. She was decommissioned on 8 November 1944, and finally scuttled on 5 February 1945.

- 40 boats and barges destroyed

Awards and decorations included:

- Three Distinguished Unit Citations

- 99th Pursuit Squadron: 30 May–11 June 1943 for actions over Sicily

- 99th Fighter Squadron: 12–14 May 1944: for successful air strikes against Monte Cassino, Italy

- 332nd Fighter Group (and its 99th, 100th, and 301st Fighter Squadrons): 24 March 1945: for a bomber escort mission to Berlin, during which pilots of the 100th FS shot down three enemy Me 262 jets. The 302nd Fighter Squadron did not receive this award as it had been disbanded on 6 March 1945.

- At least one Silver Star

- 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses to 95 Airmen; Captain William A. Campbell was awarded two.

- 14 Bronze Stars

- 744 Air Medals

- 8 Purple Hearts

Controversy over escort record

On 24 March 1945, during the war, the Chicago Defender said that no bomber escorted by the Tuskegee Airmen had ever been lost to enemy fire, under the headline: "332nd Flies Its 200th Mission Without Loss"; the article was based on information supplied by the 15th Air Force.

This statement was repeated for many years, and not publicly challenged, partly because the mission reports were classified for a number of years after the war. In 2004, William Holton, who was serving as the historian of the Tuskegee Airmen Incorporated, conducted research into wartime action reports.

Alan Gropman, a professor at the National Defense University, disputed the initial refutations of the no-loss myth, and said he researched more than 200 Tuskegee Airmen mission reports and found no bombers were lost to enemy fighters. Dr. Daniel Haulman of the Air Force Historical Research Agency conducted a reassessment of the history of the unit in 2006 and early 2007. His subsequent report, based on after-mission reports filed by both the bomber units and Tuskegee fighter groups, as well as missing air crew records and witness testimony, documented 25 bombers shot down by enemy fighter aircraft while being escorted by the Tuskegee Airmen.

In a subsequent article, "The Tuskegee Airmen and the Never Lost a Bomber Myth," published in the Alabama Review and also by New South Books as an e-book, and included in a more comprehensive study regarding misconceptions about the Tuskegee Airmen released by AFHRA in July 2013, Haulman documented 27 bombers shot down by enemy aircraft while those bombers were being escorted by the 332nd Fighter Group. This total included 15 B-17s of the 483rd Bombardment Group shot down during a particularly savage air battle with an estimated 300 German fighters on 18 July 1944 that also resulted in nine kill credits and the award of five Distinguished Flying Crosses to members of the 332nd.

Of the 179 bomber escort missions the 332nd Fighter Group flew for the Fifteenth Air Force, the group encountered enemy aircraft on 35 of those missions and lost bombers to enemy aircraft on only seven, and the total number of bombers lost was 27. By comparison, the average number of bombers lost by the other P-51 fighter groups of the 15th Air Force during the same period was 46.

A number of examples of the fighter group's losses exist in the historical record. A mission report states that on 26 July 1944: "1 B-24 seen spiraling out of formation in T/A [target area] after attack by E/A [enemy aircraft]. No chutes seen to open." The Distinguished Flying Cross citation awarded to Colonel Benjamin O. Davis for the mission on 9 June 1944 noted that he "so skillfully disposed his squadrons that in spite of the large number of enemy fighters, the bomber formation suffered only a few losses."

William Holloman was reported by the Times as saying his review of records confirmed bombers had been lost. Holloman was a member of Tuskegee Airmen Inc., a group of surviving Tuskegee pilots and their supporters, who also taught Black Studies at the University of Washington and chaired the Airmen's history committee. According to the 28 March 2007 Air Force report, some bombers under 332nd Fighter Group escort protection were even shot down on the day the Chicago Defender article was published. The mission reports, however, do credit the group for not losing a bomber on an escort mission for a six-month period between September 1944 and March 1945, albeit when Luftwaffe contacts were far fewer than earlier.

Credits: Wikipedia

Pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group at Ramitelli Airfield, Italy; from left to right, Lt. Dempsey W. Morgan, Lt. Carroll S. Woods, Lt. Robert H. Nelron Jr., Captain Andrew D. Turner, and Lt. Clarence P. Lester

Fonte: Wikipedia

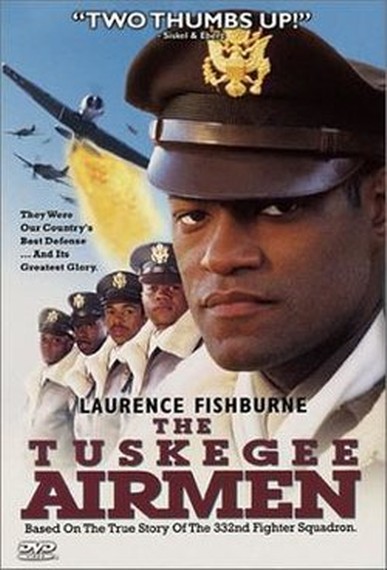

E' stato girato un film sulla storia dei Tuskegee Airmen

Red Tails è un film del 2012 diretto da Anthony Hemingway, interpretato da Cuba Gooding Jr. e Terrence Howard.

La storia, scritta da John Ridley, racconta le gesta dei Tuskegee Airmen, il primo squadrone della United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) composto unicamente daafroamericani, durante la seconda guerra mondiale

Home Page | Modellismo | Topolini | Altri Disney | Linus | Asterix | Diabolik | Giornalini di guerra | Western | Riviste | Romanzi | Mappa generale del sito